By Dan Mackenzie

We’re very grateful to Dan for taking the time to share this with us, not only as information for others, but also so that we can learn more about how things feel from a casualty’s perspective. I’ve added some contextual notes in the text for readers who haven’t been through the full rescue training. The introductory video is the most dramatic part of Dan’s experience but in reality is was just a few minutes of a nine hour journey that Dan has described so well.

Nick Barter, Clidive’s Diving Officer

Why I’m writing this

I’m not going to go into what happened on the dive itself, but I thought it would be interesting to share with the club what happens if you have a diving incident that might need a visit to the hyperbaric chamber, based on my experience on a recent dive trip. I’ve also included some things I was glad I did/had and some changes I’ll be making as a precaution for the future.

First Aid

Let’s imagine you’ve had not-your-finest-ever-dive™️ and you end up on the surface. First thing is to make yourself positively buoyant and give the emergency signal to the boat. When they come over, communicate loudly and clearly what the problem is. It might feel like nobody is acting fast enough, but that’s probably due to the adrenaline in your system.

They will put you on O2 [Clidive gives O2 first and asks questions later! NB] and somebody will be told to complete an incident form (great job Clarissa for owning this task and recording everything!). You will be asked this information probably no less than a dozen times by different people over the next several hours, so having something to refer to and/or give them (make sure to get it back from each paramedic, helicopter person, etc.) is incredibly useful. Clidive has a stash of incident forms on the boat on waterproof paper, but some new pencils/sharpies and a clipboard to make them easier to read probably wouldn’t go amiss! [The medics will also want to know details of the dive and any others in the last 48 hours or so and might consult the Dive Manager as well as the casualty’s computer. NB]

The O2 setup we have in the boats is two 7L cylinders with a normal scuba 1st and 2nd stages – O2 safe, but not a freeflow system. On the one hand this is great because we’re all very familiar with how it works, but you do have to make sure not to breathe through your nose. If you have an issue with this, pop your dive mask back on – it also helps keep water out of your eyes if it’s splashing into the boat. [Our O2 kits do have a mask and attachments for the freeflow system so we can do this if we have an unconscious diver. NB].

We carry enough O2 on our boats that in an emergency we can administer to four divers simultaneously (two second stages on each 7L cylinder) so don’t worry about running out. I was on O2 for an hour and a half, and didn’t even use up half the supply.

You will also be given water to drink but you probably won’t feel like drinking it… give yourself a schedule of taking a glug of water every 10 breaths or something similar.

Calling in the experts

If your issue is serious enough to need immediate medical attention, the cox or someone on the boat will be on the VHF radio contacting the coastguard. If you think this is unnecessary, here’s the advice given to me by the dive doctors afterwards:

- You’re probably not in the best mental state to decide

- Unless you’re 100% sure that everything is fine, err towards getting help or advice early (and if you’re that sure, why are you even breathing O2 at this point?)

- It’s easier to cancel a call for help if it’s not needed than it is to go back in a time machine to place a call 30 minutes ago when a situation deteriorates

- The emergency services and dive medics would much rather be notified early for dive incidents and help you make a non-urgent plan, than be notified once a situation has worsened and then have no option aside from an emergency plan

- If you decide not to seek treatment/help for whatever reason, carry something obvious on you for the next 48 hrs that clearly states you’ve recently been diving, who to call if someone finds you unconscious etc, and anything the paramedics should do/not do (i.e. yes to O2, no to Entonox). You don’t want to be found at some random service station on the M3 and then have them try to figure out what’s happened without knowing you’ve been diving [Clidive will always seek specialist medical advice on any apparent symptoms, even if we wait until we’re back on shore. NB]

How do you feel?

People will be doing lots of things to try and get you sorted; aside from updating the incident form, people will check in with you frequently to see how you’re doing. A habit I briefly got into was just signalling OK in the normal way. The problem here is there’s no nuance to the signal. If this happened again, I’d explain everything I’m feeling as clearly as possible, e.g. “headache is x/10, nausea is x/10, pain is x/10, temperature is x/10”.

Something I ignored for too long was that I was getting cold. While trying to control my ascent I’d opened my drysuit neck-seal to let gas out, and had let a bunch of water in. I barely even felt this for a while but, once back on the boat, I ended up sitting still, effectively in a bag of cold English sea water. It was fine for a bit, then a little uncomfortable, but I hadn’t really said much other than commenting that I’d flooded my drysuit. Part of me didn’t want to ‘make a fuss’ over something as small as being cold and uncomfortable, slightly irrational given at the same time someone was organising quite a lot of fuss in the form of a helicopter to pick me up.

Once I communicated clearly that it was causing me an issue, I was shivering almost uncontrollably and the team on the boat sprang into action, getting out an emergency blanket and ponchos and huddling close by to share body warmth.

My learning is, if you’re able to communicate, make sure you over-communicate emerging problems early, and keep doing so until some action is taken. There’s a lot going on, and while the single comment of “I also flooded my drysuit” has clear implications to you because you’re feeling the cold, that can easily get overlooked by anyone else on the boat who thinks you’re just offering contextual information.

If I’m on the other side of this in the future, I would make sure I provided this structure to a casualty where possible. But asking “how are you feeling?” is a different question to “How would you rate your headache / temperature / nausea / pain / etc. on a scale of 1-10? Has it got better or worse in the last 5 minutes?”. Specifically ask about comfort factors – the casualty may be less likely to mention these – and make sure they’re recorded too. [The incident form is supposed to be completed every 15 minutes, including specific physical tests(e.g. numbness, limb strength).NB]

Making a plan

Someone will be speaking with the coastguard/other boats relaying messages and basically trying to make the best plan to get you where you need to go. It will be tempting to keep asking what’s going on and trying to figure out what you can do to help. The answer is nothing, just let them do whatever they’re doing; if the plan changes the plan will change and, as the casualty you’re the least able to do anything. You’ll also be sitting or lying down at the back of the boat, unable to really see what’s happening or hear the radio, so just focus on your O2, water and communicating your state (especially as it changes) to the appropriate person.

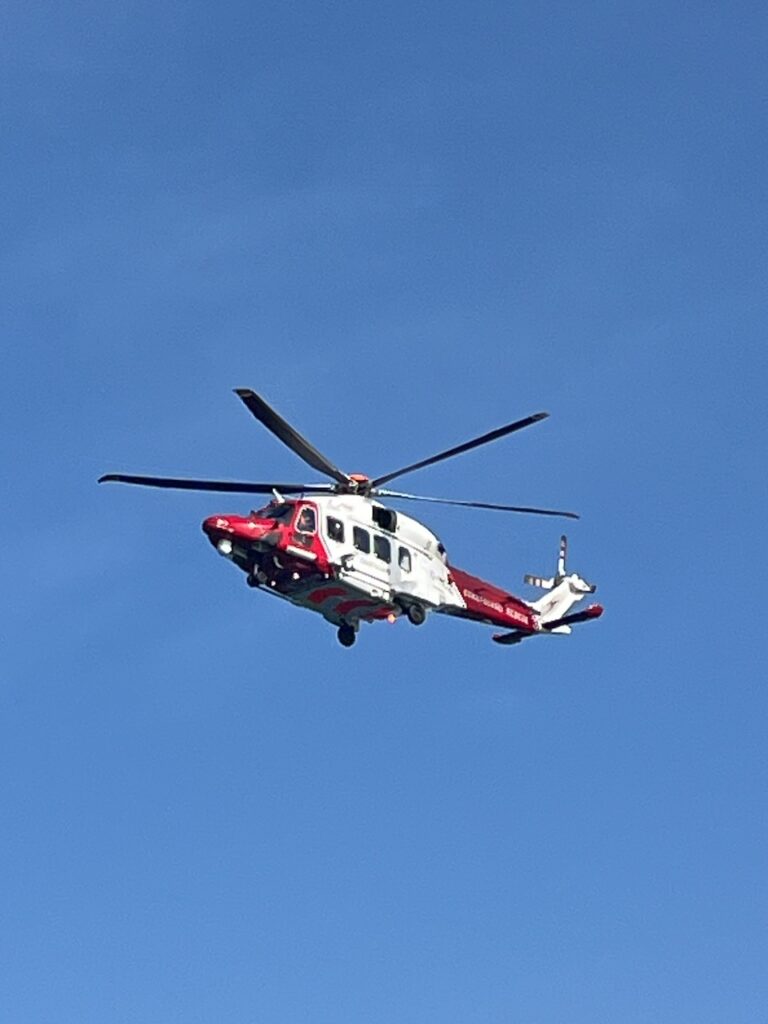

My personal journey to the hyperbaric clinic involved going from the club RIB→RNLI offshore lifeboat→helicopter→ambulance→clinic. It seems that this wasn’t particularly out of the ordinary. At each point, someone will ask you for all your details, take a set of observations and swap your O2 supply. I removed my dive gear on the club RIB, my drysuit and boots on the RNLI boat, part of my undersuit on the helicopter, another part in the ambulance and the rest in clinic before going into the hyperbaric chamber. This meant that when I got out of the chamber I had no dry clothes or shoes. Thanks Joli for thinking of this and grabbing some for me! [It’s one of the things we try to remember! NB] (Image: Nick Barter)

I happened to have just acquired a small drybox to take on the boat and will now be bringing it on every dive! Something that can fit your phone/some papers etc in it. Mine is a Pelican 1150 which I found to be the perfect size and a bungee/boltsnap through the handle keeps it in place on the boat. I’ll be adding my name and emergency contacts to the inside lid with a Sharpie, and for each dive trip will have a hard copy of a couple of other contact details for folks in the group. [The Dive Manager will always have an emergency contact for each diver, but you might prefer them not to ring your mum immediately! NB]

At the clinic

When you get to the hyperbaric clinic, there will be a dive doctor there to assess you – shout-out to Rosemary who took great care of me. She questioned me about the situation, examined me and did a set of observations, including a reflex test (tapping my elbows/knees with a small hammer). She concluded that my reflexes were “rather brisk” which meant the fluid in my joints was “more fizzy than it should be”.

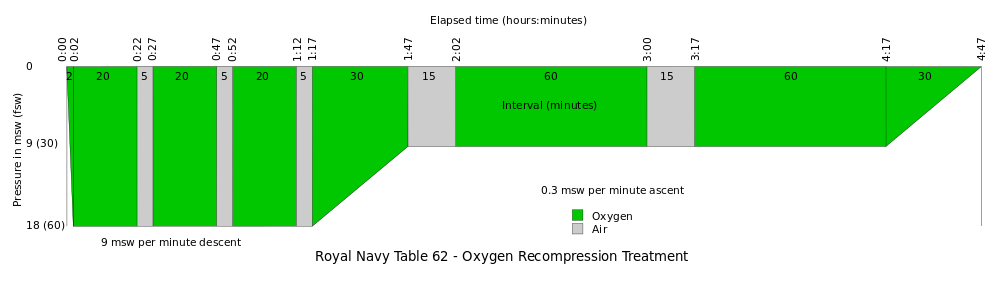

Her recommendation based on this was “Table 62+2” in the chamber. This meant that I and a lovely chap called Charlie who was there to look after me would be compressed to the equivalent of 18m underwater. I would then breathe 100% O2 with short air breaks every 20 mins or so. I’d be breathing this through a mask or hood, so that I could switch my gas without flushing the entire chamber, which could be a fire risk. The diagram below shows “Table 62”; in my case, the dive doc added two more green blocks to the first section (18msw) taking the total time to around 6 hrs.

Nitrox divers will be aware this puts my PO2 (partial pressure of oxygen) at 2.8 for around 3 hours, well above the ‘safe limit’ of 1.4 and ‘maximum limit’ of 1.6 we’re told never to exceed in order to reduce the risk of oxygen toxicity, which would bring on convulsions and seizures.

Obviously, the dive medics were well aware of this and did a great job explaining that the likelihood of this would be significantly reduced as I wouldn’t be moving much in the chamber, but also that convulsions, etc. are not a huge problem in the controlled environment of a chamber, compared to underwater when you have to keep a mouthpiece in to avoid drowning. If convulsions did occur, Charlie was on hand to remove my O2 hood, and make sure I was okay. They could then reduce the simulated depth in the chamber or shorten the duration between air breaks to provide O2 without further convulsions as needed.

Into ‘the pot’

I got a thorough briefing, signed some consent paperwork, and changed into the hyperbaric scrubs provided. Nothing with a battery can go into the chamber (electronics don’t always love pressure and we definitely want to avoid sparks in a potentially O2 rich environment), so no wifi, airpods, or netflix. They do have an intercom which the control room kindly played the radio through so we had some music to listen to.

I’d use this time to quickly call/message anyone who you might want to get in touch with while you’re in there and give them the contact details of the chamber operator (possibly vice versa as well). As mentioned above, in the future, I’ll be keeping a card with at least a couple of the contact details of folks I’m with in my drybox. It’s much easier than trying to guide someone through navigating your phone over an intercom.

Also grab a book… they had a nice little bookshelf to peruse.

I didn’t really have any mental picture of what a chamber looked like inside, but it’s a metal tube roughly the size of a van with a single bed on each side. There’s a main chamber, an ‘entry lock’ that can be de/re-pressurised while you’re in there to get other things/people through, and a ‘med lock’, which is a small port that can be equalised and sealed from either side to pass small items through (like cups of tea).

The initial ‘blow down’ to depth feels much quicker than it is, it’s a rather gradual ascent, but I felt like I had to equalise almost every half metre of depth change, it’s also rather loud, but they should have some ear defenders for you to use.

For the O2 administration, if you have a choice between a ‘bib mask’ or a ‘hood’, I’d go with the hood, as it allows you to talk and seems more comfortable to me, although a little more of a hassle if you want to lie down. If you have a beard like I do, you have to use the hood because the bib mask won’t seal properly. Think a drysuit neckseal system clipped to a clear upside down flexible bin on your head. It has two tubes attached, one to put O2 in and one to exhaust it out. The flow rate is adjustable and when they initially put it on everything is super loud, but ask them nicely and it can be adjusted down to make it more pleasant. You just need enough flow that the visor isn’t misting when you breathe out apparently.

The second half was at a shallower depth (9m) with longer sessions on O2 (less pressure means lower PO2, so you can tolerate a longer session more safely) and then a gradual slow ascent to the surface. For some parts of this, your chamber buddy is also on O2 so it can be tricky to talk, making it a perfect time to catch up on a bit of reading.

Creature comforts

They’ll look after you, offer you water/tea/coffee and snacks, which you can consume during your air breaks; and they’ll give you menus and order your choice of (free!) food from local takeaways. If you want a laugh, ask for a packet of crisps and it’ll arrive through the med lock totally squished from the pressure (shrink-wrapped crisps still taste the same though!).

If you need to use the loo, they’ll pressurise the entry lock to chamber pressure, then you can go in there to get some privacy, do what you need to do and return to the main chamber when it’s resealed. Various pee pots, potties, etc. are available, so no need to worry about having to hold it for 6 hrs.

The operator on the outside has a camera and intercom so they can chat with you and are great at talking you through what’s happening when. Sometimes it can be tricky for them to hear you if you’re in the O2 hood, but your buddy in the chamber is able to help you be understood, and it’s relatively easy to have a conversation with each other even when the hood is on.

It’s not painful, it’s not particularly stressful, it can be a little tedious and boring, but doesn’t have to be (I learnt loads about the previously unfamiliar world of commercial diving – thanks Charlie!), and it sure is better than the alternative.

Two common side effects they’ll warn you of are “oxygen cough” and “Hyperbaric Induced Myopia”. The cough is just a normal cough and goes away after a day or so; the myopia (nearsightedness) is usually minor, but also resolves within two weeks. If you wear glasses though, don’t try and change your prescription or get an eye test in this period because the result may very quickly be incorrect.

What happens next?

Once our chamber ride was finished, the dive doc came back to the clinic (sorry Rosemary if I disrupted your evening plans!) and ran through another set of checks and observations. In my case my reflexes were back to normal again, so no Spiderman-like brisk reflexes for the foreseeable future. Once given the all clear, I was good to go, after signing a couple forms and papers, and getting changed back into the normal clothes Joli had brought me.

No alcohol for a day or two, no flying for 72 hrs, and no diving for the next four weeks, but after that all fine.

A team effort!

I’m very thankful that we have such a great infrastructure in place within our diving environment here, from the Clidive folks onboard the boat and all who helped train them, to the skipper of a nearby boat who helped relay radio messages to the coastguard when they couldn’t hear us, to the crew of RNLI Weymouth who used their offshore lifeboat as a winching platform, to the helicopter team that took me to Poole, and ambulance that transferred me to the NHS Diving & Hyperbaric Medicine unit – the ‘Diver Clinic’ – who assessed and treated me as quickly, kindly and professionally as I could have ever hoped for. Thank you all!

It’s frankly not an experience that I have any plans to repeat, but I hope sharing what it involved provides you with an interesting read, helps if you ever find yourself in a similar situation and encourages you if have any desire to get involved with or support the various organisations mentioned above.

Further reading on Oxygen Toxicity: https://www.diverite.com/articles/oxygen-toxicity-how-does-it-occur/

We are an LGBTQIA+ friendly club

We are an LGBTQIA+ friendly club