By Thomas Mosk

For divers, our buddy check is a mantra: 220 bar, smells good, tastes good, no fluctuations…

But on the first dive of this trip, something was off. Everything looked normal—but this first dive would turn out to define the expedition.

A Celtic Welcome

CLiDive Yellow, our trusty RIB, made its way across the Channel, onto the ferry and down to Brittany—the southernmost of the six Celtic nations.

Concarneau, or Konk-Kerne in Breton, became our base. A fortified harbour town steeped in history. Concarneau offered more than just diving: fantastic crêpes on our first evening and the Breton flag, Gwenn ha Du, fluttering in the breeze.

The First Dive: The Pietro Orseolo

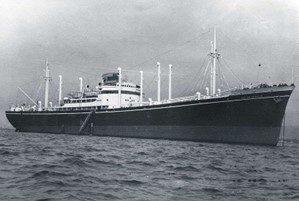

Friday dawned bright. At 10:00 we cast off, our destination: the wreck of the Pietro Orseolo. Once an Italian cargo ship, captured by German forces, it was sunk by British Coastal Command on 18 December 1943.

We kitted up, did our buddy check, and one by one, ten Clidivers rolled into the Atlantic. The descent should have been the easy part.

It wasn’t.

Nick B surfaced early, complaining of foul-tasting air and a light headache. Others followed, reporting dizziness. Back on board, we sniffed our cylinders. A faint odour—dry plastic, rubbery—lingered. Something was wrong. Very wrong.

Our Chief Air Sniffer Smells Trouble

Back in Concarneau, we raised the issue with the local dive operator. He promised us fresh fills. Yet the next morning, Cathy—by now promoted to “Chief Air Sniffer”—returned with troubling news: the smell persisted.

Air is a diver’s lifeline. Without air, the expedition would have been over.

But fate had a twist. On the Glénan Islands, 45 minutes away, the local dive school had cancelled their weekend operations. Better still, they had one of the most ingenious, sustainable, wind-powered high-pressure storage systems I had ever seen.

Cylinders filled in five minutes, and after a quick coffee, we were ready to go. Our misfortune had carried us to an unexpected saviour.

Getting air – photo by Thomas

Diving Resumes

From then on, Brittany delivered in spades. Clear skies, Glénan air fills, and dives that blended history with wildlife. We explored a variety of sites:

Le Run (Wall) – My favourite dive! What could be better than diving with the two “rainmakers of visibility,” Michael and Steve, and playing their octopus and nudi spotter? I found two Blue-and-Yellow nudis! Meanwhile, Nick S learned that seals have zero respect for personal space—they didn’t stop at his fins (groin guards highly recommended).

- War Captain (Wreck) – This British steam freighter struck a rocky shoal at full speed in 1917 and broke apart on both sides. Carried by the Atlantic swell, one diver ended up on the very rocks that had doomed the ‘War Captain.’ Others became tangled in the kelp forests, but those who reached the wreck were rewarded with glimpses of its propeller, boilers, and winches.

- Le Galaxie (Wreck) – Following a navigational error, the Galaxie sank in 1998. On the dive, The Galaxie lay eerily still in the green water; at 30 m, with limited visibility, it felt strangely quiet, as if time had paused around the wreck.

- Le Gluët (Wall) – Wind always matters in Brittany, but the Atlantic swell can be just as decisive. Waves kept us from an exposed wall, so we explored Le Gluët instead. Underwater, octopus sightings sparked heated debates—five or six? Without a referee, the mystery remains.

After a few turnarounds retrieving our man-overboard buoy, ‘Bob,’ to train our coxes, we rewarded ourselves with a royal seafood feast at Le Chantier — oysters, clams, langoustines, crab, winkles, whelks, and lobster. Cheers!

Reflections: Lessons from Bad Air

“Bad air” is a phrase no diver wants to hear. Carbon monoxide — the silent killer you can’t smell — is one possible danger. Just as insidious, though easier to notice if you’re alert, are oil vapours, plastic notes, or odd odours. Regulators often have a faint “plastic” tang that masks the warning signs.

Perhaps we do need a “Chief Air Sniffer” on every trip. More seriously, smelling the air after a fill—or randomly checking cylinders—is good practice. And buddy checks aren’t a mantra to rattle through. They are a deliberate, step-by-step safeguard. Smell the air. Always!

We are an LGBTQIA+ friendly club

We are an LGBTQIA+ friendly club